In July of 2022 a team of U.S. and Peruvian archaeologists and conservators unearthed astonishing mural paintings dating to the late Moche period (ca. 600-800 CE) in the Nepeña Valley of Peru.

The Zoology Preparation Lab specializes in dissecting and preparing vertebrates for the zoology research collection. Here, you’ll find dozens of Northern Flickers (Colaptes auratus) that were killed by cats, over fifty shrews (Sorex sp.) from Wyoming preserved in ethanol and the newest addition—an endangered mountain tapir (Tapiris pinchaque) skeleton from the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo. Working to ensure these specimens are preserved to last is a zoology preparator, a team of volunteers ready to get their hands dirty and a crew of flesh-eating beetles (Dermestes maculatus) itching to eat flesh off of skeletons.

Although few people prefer to work in dissection, zoology preparation labs are the lifeblood of an active zoology collection. Preparators are responsible for ensuring specimens will last centuries for future generations of scientists to study and the public to see.

Pañamarca, the southern-most monumental center of the ancient Moche society of Peru’s north coast

Pañamarca contains an array of adobe monumental platforms, walls and temples. The first mural discoveries at the site were revealed to the world in the 1950s. These included a famous mural of a Moche priestess, which was one of the first discoveries to hint at the power that women held in Moche society. Since then, remarkably little work was done at the site until 2010, when Lisa Trever and her team documented paintings on numerous structures, indicating that Pañamarca was once a vibrantly painted marvel with vividly colored scenes of human and divine figures engaged in a dramatic array of ceremonies, pageantry and epic narratives. Some of the most remarkable discoveries in 2010 were located within a monumental pillared hall that was painted and repainted over the centuries. Excavation this past July continued in this structure, where exciting depictions of southern Moche life and lore continues to unfold.

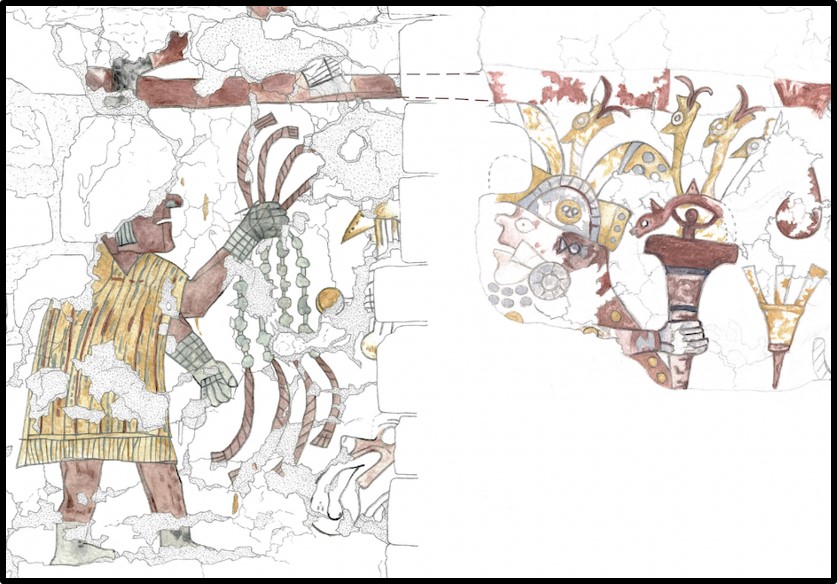

Newly uncovered paintings portray strange beings — including a two-faced man (pictured here) never before documented in Moche art, women displaying colorful spun threads and weaving tools and extravagantly rich processions of well-dressed individuals. Remarkably, the leader of the procession is another probable image of the Moche priestess or another high-ranking woman wearing similar apparel. Because of conservation concerns and time constraints, only a portion of this figure was revealed in 2022, but her headdress, necklace, ear spools and the serpent-head at her waist — possibly from her belt, seen next to the end of what is likely one of her braids — makes her immediately recognizable. She faces a figure uncovered in 2010 that is dressed in a tunic typical of highland Peruvian cultures and not usually seen on the coast. It is clear that the highly-regaled female and the tunic-clad man are the focal points of the scene on this corridor wall, yet we still do not know what she is holding in her left hand as she addresses this foreign man. This will be revealed in excavations in July 2023. Nonetheless, this exciting discovery of the seemingly diplomatic interaction of highland and coastal people is not typical of Moche art, and in fact, adds a new understanding of multiculturalism in Moche society at the southern frontier.

Famous mural of a Moche priestess found at Pañamarca.

Figure of highly-regaled female and tunic-clad man are the focal points of the scene on a corridor wall unearthed at Pañamarca.

What is not new, however, is the recognition that women held great power in Moche society. In addition to the Pañamarca priestess mural published in 1959, and the many paintings of women in roles of power on Moche fineline ceramics, the adobe chamber tombs of at least eight so-called priestesses have been unearthed at the site of San José de Moro, 300 km north of Pañamarca. These tombs were furnished with many fine ceramics, copper-gold adornments and human and llama sacrificial offerings. At the site of El Brujo, the Señora de Cao — an elite woman buried with gold war clubs and atlatls (spear throwers) — demonstrates that gender roles in Moche society did not conform to Western binaries. The new paintings at Pañamarca add to the growing corpus that demonstrates the important roles of women as makers and as leaders in Moche society.

Once these colorful paintings are exposed, however, they need to be covered back up almost immediately. The dry desert environment of coastal of Peru is responsible for the impressive preservation of the murals in the first place. The region receives less than an inch of rain a year, which aids in preserving buried artifacts and earthen architecture exceptionally well. Yet, if murals, earthen reliefs, or other delicate earthen architectural features are left exposed the relentless winds that carry abrasive sands and harsh UV rays from the sun will destroy them in a short amount of time.

The 2022 field season at Pañamarca was supported by The National Geographic Society and Columbia University with assistance from the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. Beginning in 2023, the Avenir Conservation Center at the Museum has dedicated seven years of funding to continue this collaborative project. It is crucial that the conservation needs of the painted architecture remain the top priority of the archaeological fieldwork. The archaeological team is responsible for the research plan for where to dig. Once determined, the conservation team constructs temporary wind blocks to ensure the painted surfaces remain protected while exposed. The archaeologists work to complete the excavations to the point where the conservation team comes in to remove the dirt that covers the painted surface, all while stabilizing and consolidating the murals. Once the murals are exposed and thoroughly documented with photography, photogrammetry, field notes and pencil and watercolor drawings, they are carefully reburied, thus ensuring these invaluable documents of the ancient past endure for the next 1500 years.

Members of the team working on site.

Overall, the new discoveries confirm our theory that Pañamarca was a place of unusual creativity and a crucible for artistic invention. The artists and patrons of Pañamarca did not conform to what otherwise is thought to have been a very rigid society and artistic style. Yet, these latest finds are just the tip of the iceberg. We could see that many more earthen wall paintings remain in remarkably good condition just below the surface at Pañamarca. We are excited to continue to document the painted surfaces of the hall of painted pillars in 2023. Additionally, other areas of the site will be explored to bring further understanding to this important southern Moche monumental center and the secrets it holds.