By: James Hagadorn and Ellen Roth

Maps are everywhere. You’ve used tiny ones to guide you through city streets on your smartphone, or perhaps seen them on a larger scale — adorning visitor centers at national parks, ski resorts and museums. These visual companions, often representing a bird's-eye view of satellites or airplanes, give us a sense of the terrain and the conditions ahead.

But maps are more than just navigational tools. They can help us time travel — offering a bridge between our past and future. Earth and climate scientists craft maps to illustrate deep time and to communicate the face of our planet in the millennia to come. At the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, so-called "paleomaps" invite you to explore the past in Prehistoric Journey or other planets in Space Odyssey.

Read more: Space Exploration Day: Things to do at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science

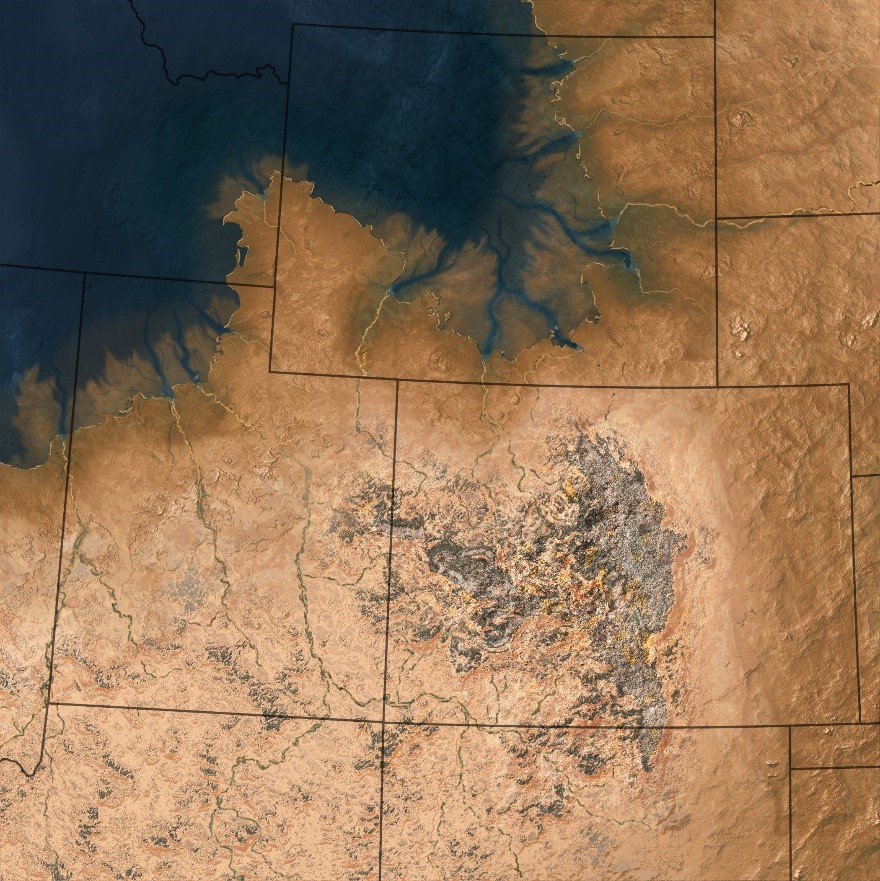

Satellite-like map of the western U.S. during the Permian, around 250 million years ago, when the ancestral Rocky Mountains and dusty deserts dominated Colorado’s landscape. (Photo/ Hannah Bonner)

Maps that allow you to travel through time sound incredible, right? Now, here's the catch: while we've made strides in mapping Earth's distant past and its unfolding future, we missed crucial viewpoints — yours, mine and our community's.

For instance, imagine spotting a huge white oval on a satellite map of Argentina. How would you tell whether it’s a frozen tundra lake, a salt-filled desert playa or something else entirely? Now think about the unfamiliar features you might encounter on a satellite map of Colorado during the Jurassic Period or how Colorado may appear 200 years in the future. Visualizing the terrain and inferring the climate of these settings is difficult, given we’re navigating the unfamiliar without context.

To address these map challenges, we teamed up with our CU-Boulder colleagues, Hannah Bonner and Leilani Arthurs, to conduct interviews with museum and park visitors. Our mission: to gauge their knack for reading maps that depict ancient terrain and climate. Armed with a collection of paleomaps, we engaged groups in places where such illustrations are common: Garden of the Gods, the Natural History Museum of Utah and our very own Denver Museum of Nature & Science. With our newfound insights, we aimed to improve the relationship between maps and their viewers.

Denver Museum of Nature & Science collaborator Hannah Bonner surveying audiences about map perceptions. (Photo/ James Hagadorn)

What did we find?

We learned that when faced with an unfamiliar satellite-style image of a foreign landscapes, the general public can readily identify three large-scale landscape features, such as mountains and oceans. But they wrestle with discerning subtler features, such as rivers, volcanoes or plains. For comparison, scientists versed in maps can typically spot around five such features. Surprisingly, both public and scientific audiences have a hard time interpreting climate from maps — no matter their experience or expertise.

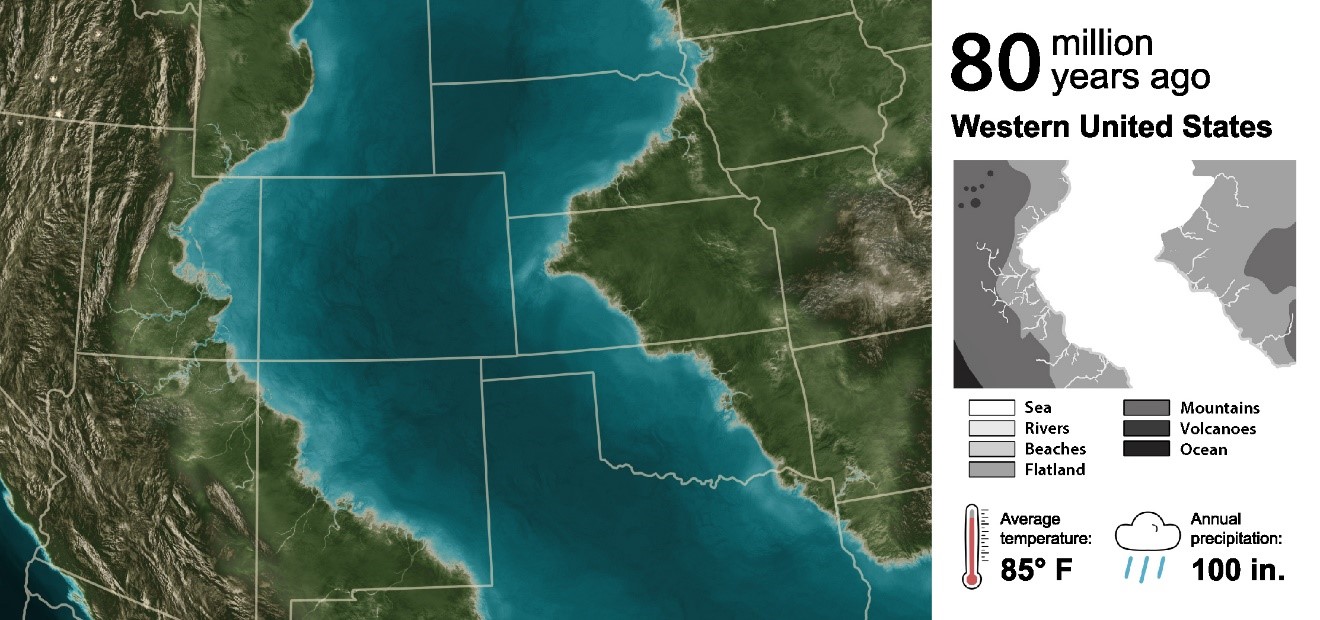

To make interpreting spatial data more intuitive, we discovered that audiences gravitate toward maps that employ shading to convey depths of water bodies, that have higher contrast colors and that include explicit indications of climate elements, such as temperature and rainfall. The exemplary map below incorporates these features, depicting what the Rocky Mountains looked like 80 million years ago when Colorado was underwater.

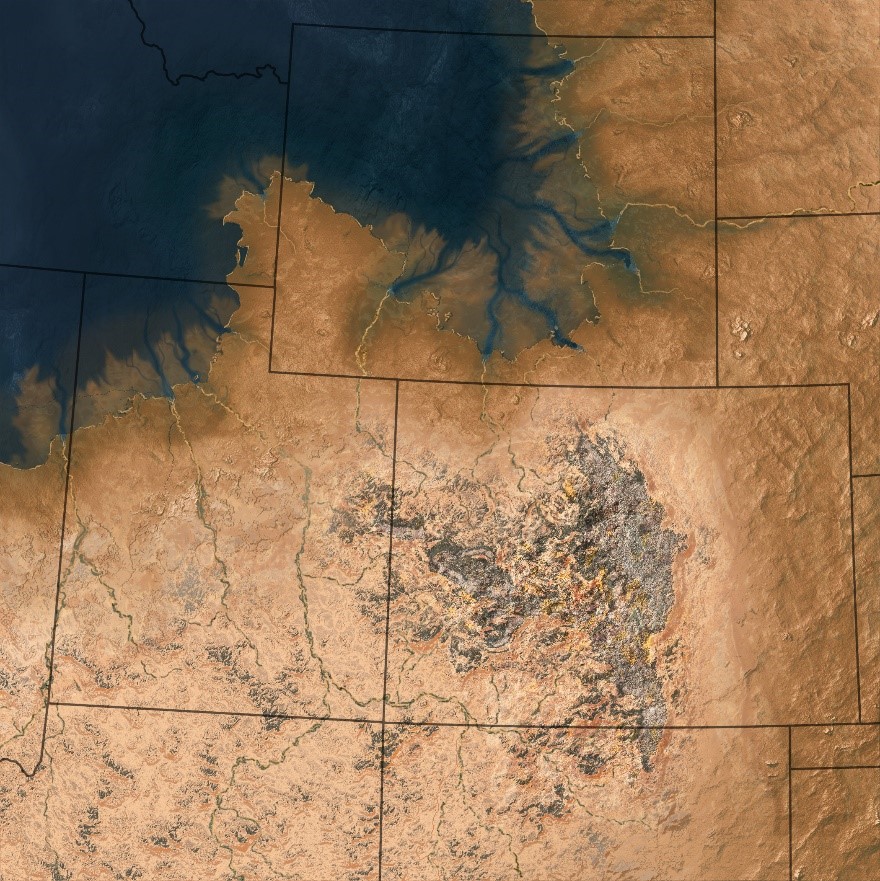

Enhanced satellite map of the western U.S. during the Cretaceous, around 80 million years ago, when much of the west was submerged under a shallow sea. (Photo/ Hannah Bonner)

Maps are catalysts of curiosity

In our survey study, we also learned something more intuitive: Maps are catalysts of curiosity. They stir questions about our planet's past, present and the untrodden paths of the future. Whether derived from modern satellites or created by deep time artists, maps have a remarkable ability transcend language, education and experience, beckoning us to probe the "how" and the "why" of our changing world and infinite cosmos.

Want to explore more? Dive into our article in the scientific journal, GSA Today. And stay tuned for the next chapter, as our Museum’s paleomapping team integrates these findings to make the next generation of maps for our community.

About the authors: James is the Tim & Kathryn Ryan Curator of Geology and Ellen is the Manager of Community Research & Collaboration. Both Ellen and James are long-time museumophiles who are passionate about leveraging data to help improve how we connect our community with science and nature. This work represents the first peer-reviewed publication between their two divisions at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science.