Why Is Castle Rock So Prominent?

How Museum Scientists Uncovered a Geologic Mystery

Drivers on I-25 near the town of Castle Rock have likely marveled at iconic Castle Rock, towering over its namesake city. Or perhaps you’ve hiked through Castlewood Canyon State Park, to see the stunning geological formations across rolling grasslands.

But why do the imposing flat-topped buttes appear the way they do? A new study by Denver Museum of Nature & Science scientists helps answer that question, shedding light on why these exposed sedimentary rocks, which would generally be prone to erosion, have lasted for tens of millions of years and continue to be prominent to this day.

Research, published in the latest issue of The Mountain Geologist, reveals Castle Rock’s exceptional durability is actually because of the presence of two unique and captivating gem minerals, opal and agate. (Photo/ Jeff Albright)

The study, authored by Museum Research Associates Dr. Mark Longman and Joan Burleson, along with the Museum’s Tim & Kathryn Ryan Curator of Geology, Dr. James Hagadorn and published in The Mountain Geologist, reveals Castle Rock’s exceptional durability is actually because of two unique and captivating gem minerals, opal and agate.

Although the Castle Rock buttes are conglomerates — a type of rock that normally breaks down easily, usually decomposing after just a few millennia in the elements — the conglomerates near Castle Rock don’t crumble so easily. This paradox intrigued career petrologist Dr. Longman.

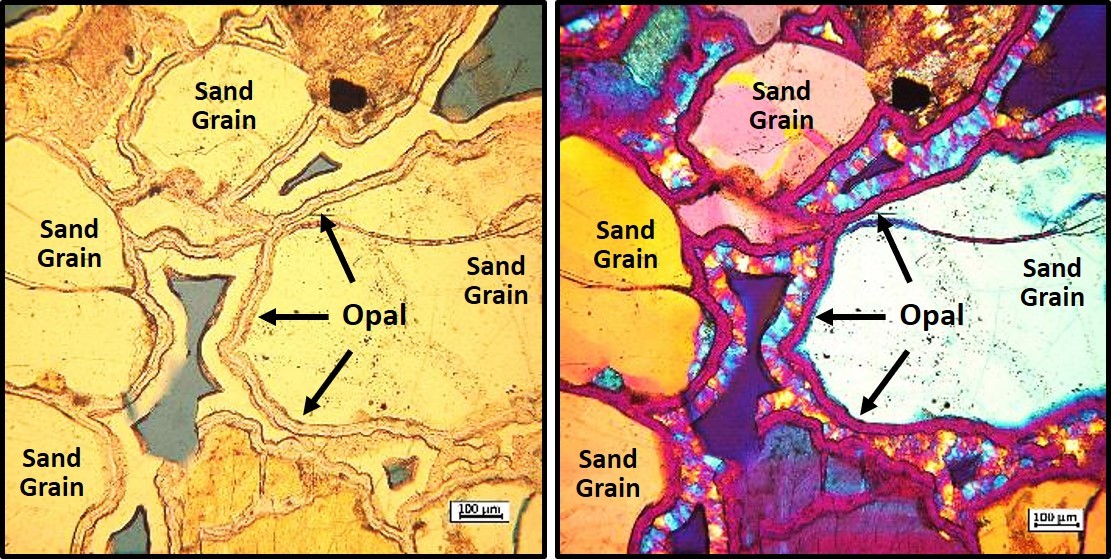

To solve the mystery, Longman analyzed wafer-thin sections of Castle Rock’s strata on a specialized light microscope, identifying the different grains and cements in the rock. Unlike most conglomerates in Colorado, every sand grain and pebble in these rocks is encased in a rind of opal and chalcedony, a mineral also known as agate. These minerals cement the particles together to make a very durable rock — one that is harder than most concrete.

Microscope image of a thin slice through the Castle Rock Conglomerate, showing the rind of opal that surrounds the rock’s grains. (Photo/ Mark Longman)

How did such a special conglomerate come to be? About 36 million years ago, volcanoes in the Sawatch Range near Buena Vista spewed large volumes of ash and volcanic debris to the several-county area around Castle Rock. These deposits of volcanic ash, glass and rock fragments cemented together to form a silica-rich rock known as the “Wall Mountain Tuff.”

James Hagadorn and Mark Longman examining a boulder-sized clast of the Wall Mountain Tuff in the Castle Rock Conglomerate. (Photo/ Joan Burleson)

Once there, groundwater percolating through the Wall Mountain Tuff dissolved some of its silica-rich minerals. This water gradually seeped into the conglomerate where the silica precipitated as opal. This opal coated and cemented the grains and clasts together. Later, more silica-rich water seeped into the conglomerate, depositing the hard fibrous chalcedony.

Over 30 million years later, rivers and streams such as Cherry Creek carved canyons into this rock formation, including Castlewood Canyon. Such erosion also left behind orphaned “islands” of rock that today make up buttes such as iconic Castle Rock.

Cherry Creek canyon at Castlewood Canyon State Park, whose walls are flanked by the Castle Rock Conglomerate. The bridge for State Highway 83 is visible in the distance. (Photo/ Joan Burleson)

An excellent area to view these opal- and chalcedony-cemented sandstones and conglomerates is in Castlewood Canyon State Park just south of Franktown. Castlewood Canyon State Park is well known for its amazing geology, steep-walled canyons flanking Cherry Creek and excellent hiking trails.

If you want to see the opal-cemented geological wonders for yourself, consider making a trip to Castlewood Canyon State Park where you can easily see these incredible rock formations. Please note, however, that collecting rocks and minerals in these parks is restricted, so you can look but don’t take anything with you!

Remnant of the 70-foot-tall Castlewood Dam in Castlewood Canyon State Park, showing the stone block construction that typified the dam before its central portion washed away in the flood of 1933. (Photo/ Joan Burleson)

About the authors: Joan Burleson and Mark Longman are longtime Museum supporters and Research Associates in the Department of Earth Sciences and James Hagadorn is the Tim & Kathryn Ryan Curator of Geology in the same department.