How the Museum Received its Largest Research Grant Ever

In the world of paleontology, there are few moments that can match the electric thrill of an exceptional find — especially a find that holds the power to reshape our understanding of the history of life on Earth. For Dr. Tyler Lyson and his team, such a moment came in 2016 at Corral Bluffs near Colorado Springs. Their exhilarating discovery — a remarkably complete mammal skull, dating back 65 million years, only a few thousand years after the dinosaurs walked the Earth — would not only change the course of their research but also lay the groundwork for the largest research grant ever received by the Denver Museum of Nature & Science in the summer of 2023.

The discoveries at Corral Bluffs ultimately paved the way for the Denver Museum of Nature & Science to receive a prestigious collaborative research grant from the National Science Foundation's Frontier Research in Earth Sciences program. The nearly $3 million collaborative research grant, led by the Museum with a portion over $1,280,000, is the largest research grant ever received by the Museum.

Tyler Lyson and Ian Miller examine a fossil bearing concretion. (Photo/ Rick Wicker)

Here’s how it happened:

In late summer of 2016, after months toiling in the scorching heat, maneuvering digs through torrential rainstorms and countless hours breaking apart large rocks and boulders with picks, shovels and jackhammers, Dr. Lyson split open a rock that would reveal a remarkably complete Carsioptychus skull. An extinct javelina-sized plant eating mammal, the Carsioptychus, had roamed the Earth only a few hundred thousand years after the non-avian dinosaurs went extinct. Laughter and cheers erupted while high fives flew, the joy and excitement rising above the dust of the broken rocks.

The team — which included Dr. Ian Miller, geologist Ken Weissenburger and Museum volunteer Sharon Milito — had unearthed more than just a fossil: they had discovered the first of many clues that will help scientists to unlock the secrets behind the rise of mammals. The fossils at Corral Bluffs provide a guide for understanding the origins of how and when modern ecosystems rebounded after the Cretaceous/Paleogene (K/Pg) mass extinction that wiped out the giant dinosaurs.

Aeon Way-Smith and Laurel Butterworth excavate a plant quarry at Corral Bluffs in 2017. (Photo/ Rick Wicker)

The journey that ultimately led Dr. Lyson and his team to the breakthrough moment had started two years earlier when Dr. Lyson joined the Museum in 2014 as the Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology. Coming to the Museum, Dr. Lyson wanted to answer important scientific questions, and one of the biggest unanswered questions was what happened in the first 1 million years after the giant dinosaurs went extinct. To find answers he would need to find complete fossils from this critical interval of time. But at first, he didn’t know exactly where to look.

“We were looking at geological maps of Bolivia, Argentina and other places around the world. But we thought, ‘well, we should probably look in our backyard before we spend a lot of money going somewhere halfway across the planet.’ And funnily enough, we ended up making the big discovery right here in Colorado, within the city limits of Colorado Springs,” said Dr. Lyson. “It’s crazy because you never think these big discoveries are going to happen in your own backyard.”

Interns Eldon Panigot and Emily Burns work alongside postdoctoral scholar Holger Petermann at Corral Bluffs. (Photo/ Rick Wicker)

Dr. Lyson said the key to finding fossils at Corral Bluffs was looking for concretions, a special type of rock that forms around fossils. Dr. Lyson compared finding the fossils inside concretions to “opening an oyster shell to find a pearl.”

“When we started uncovering mammal fossils at Corral Bluffs, it was like going to the optometrist and the slide flipped on and everything came into focus,” said Dr. Lyson. “Suddenly, it was game on, and we knew exactly what to look for. All we had to do was find these special concretions, crack them open, and see what amazing fossils were inside.”

After finding the Carsioptychus, within a matter of minutes, the team found more mammal skulls belonging to different species. From there, the scientists used different methods to date the rocks in which the fossils were found, making it possible to track how and when species and ecosystems recovered from the extinction event. The site's unique preservation of diverse species — both plants and animals — afforded a rare glimpse into past ecosystems immediately before and after the asteroid hit Earth that caused the K/Pg mass extinction 66 million years ago. Here roughly 75% of all species on Earth went extinct in a geologic instant.

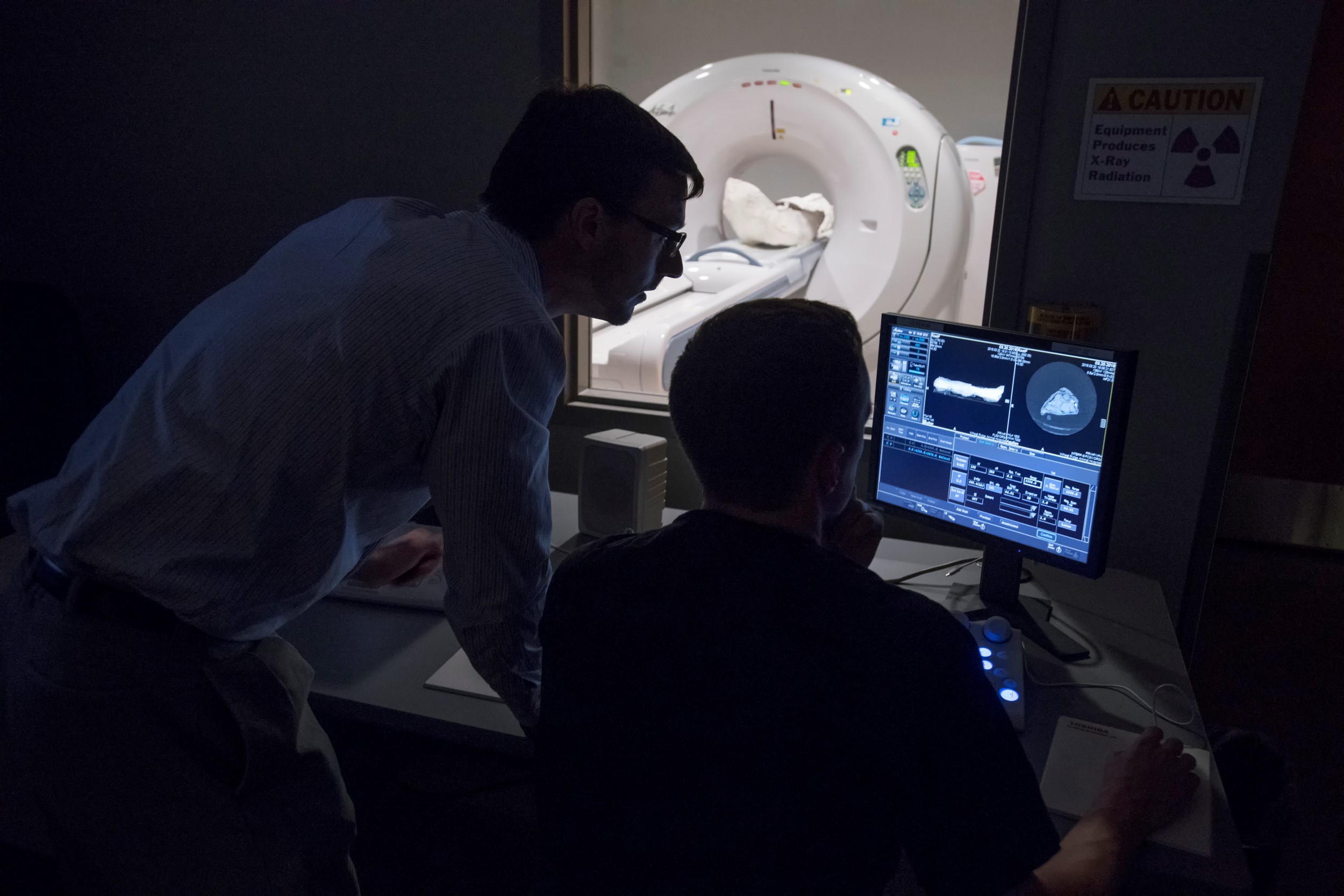

Researchers examine preliminary Computed Tomography results of a Corral Bluffs fossil at the Northglenn Veterinary Hospital. (Photo/ Bryce Snellgrove)

This K/Pg mass extinction event completely changed the trajectory of the evolutionary tree of life, leading ultimately to the formation of today’s extraordinary mammal diversity. The fossils found in Corral Bluff, dating back to the aftermath of the K/Pg mass extinction, represent a natural laboratory where ecosystem reorganization can be studied in higher resolution than ever before.

Dr. Lyson said the NSF grant will allow the Museum to pull together “more people to do more science.” Now, he’s building out the team with people coming together with different skills sets, such as digital fossil preparators, mechanical preparators, geochemists, paleobotanists, geochronologists and vertebrate paleontologists specializing in mammals, turtles and crocodilians. The research grant includes 12 scientists from several collaborating institutions, including Brooklyn College - City University of New York, College of Charleston, Colorado College, Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, University of British Columbia, University of Colorado Boulder, University of Oregon and University of Wyoming.

With this significant financial boost, this multidisciplinary team of scientists will dig into the rocky soil of our planet's history to answer important, unanswered questions about how life rebounded after Earth’s darkest hour.

This browser is no longer supported.

We have detected you are using a less secure browser - Internet Explorer.

Please download or use Google Chrome, Firefox or if using Windows 10, you may also use Microsoft's Edge browser.