Discover the latest news, explore exhibits and connect with the natural world. Visit Catalyst Online

Members receive free admission to the Museum 364 days a year! Become a Member

Take your Museum journey home with you. Visit the Museum Shop

Rocks Are a Surprisingly Common Source of Deadly Substances

Poison originates in two places. The major sources are organisms such as animals, plants and fungi. But the other common source lies beneath our feet – rocks and minerals.

One of the most deadly of these minerals is named after our state. Coloradoite occurs in Rocky Mountain gold deposits, forming where hot, metal-rich fluids migrate and cool in networks of cracks in rocks. This is a "telluride" mineral because it is composed of tellurium bonded to mercury. Whereas tellurium is only mildly toxic, mercury is dangerous because it wreaks havoc with our central nervous system. We are exposed to mercury through various sources, including large fish such as swordfish, tuna, and mackerel; runoff from abandoned mines; and even in the air, from coal fired power plant emissions. Although there are different types of mercury compounds, all are notable because mercury is one of the few metals that readily passes through our protective cell membranes and accumulates in fatty tissue stored in the body.

Coloradoite from the Rex Mine in Boulder, Colo. (Photo/ Rick Wicker)

Cinnabar is mercury bonded to sulfur. It forms the same way as coloradoite, and it also occurs in hot spring deposits. Exposure to mercury vapors is the primary hazard, though inhaling the dust will also lead to illness. Spanish cinnabar miners were noted for their short life spans because they heated the cinnabar to recover the metallic mercury, releasing vapors. Hat makers were also exposed to mercury vapors when they used mercury nitrate to turn animal pelts into felt. They developed psychoses and tremors, giving rise to the term "mad as a hatter."

Cinnabar from Terlingua, Brewster, Tex. (Photo/ Rick Wicker)

Orpiment and realgar are varieties of arsenic bonded to sulfur. They form in the same way as coloradoite and cinnabar, and can even be found in Yellowstone's hot springs. Orpiment, with its bright yellow-orange color, was historically used as a pigment, as a component of fireworks, as a poison on arrow tips, and together with realgar are still used in semiconductors, linoleum, and some glass products. Arsenic is notorious because it has been used for centuries to intentionally poison people, often family members among the wealthy and powerful. Because we can't see, taste, or smell arsenic when mixed into food or water, it was the perfect "inheritance powder."

Orpiment from the Getchell Mine in Humboldt, Nev. (Photo/ Rick Wicker)

Today, we rarely see deliberate arsenic poisonings, but many drinking water supplies, including some in the United States, contain high levels of arsenic and present a hazard. This contamination is currently a major problem in Bangladesh, where most drinking water is heavily tainted with arsenic. On Colorado's Western Slope, soils derived from the arsenic-rich Mancos Shale present a similar risk. Surface waters that drain through locales where these soils have been disturbed are regularly monitored for arsenic leaching.

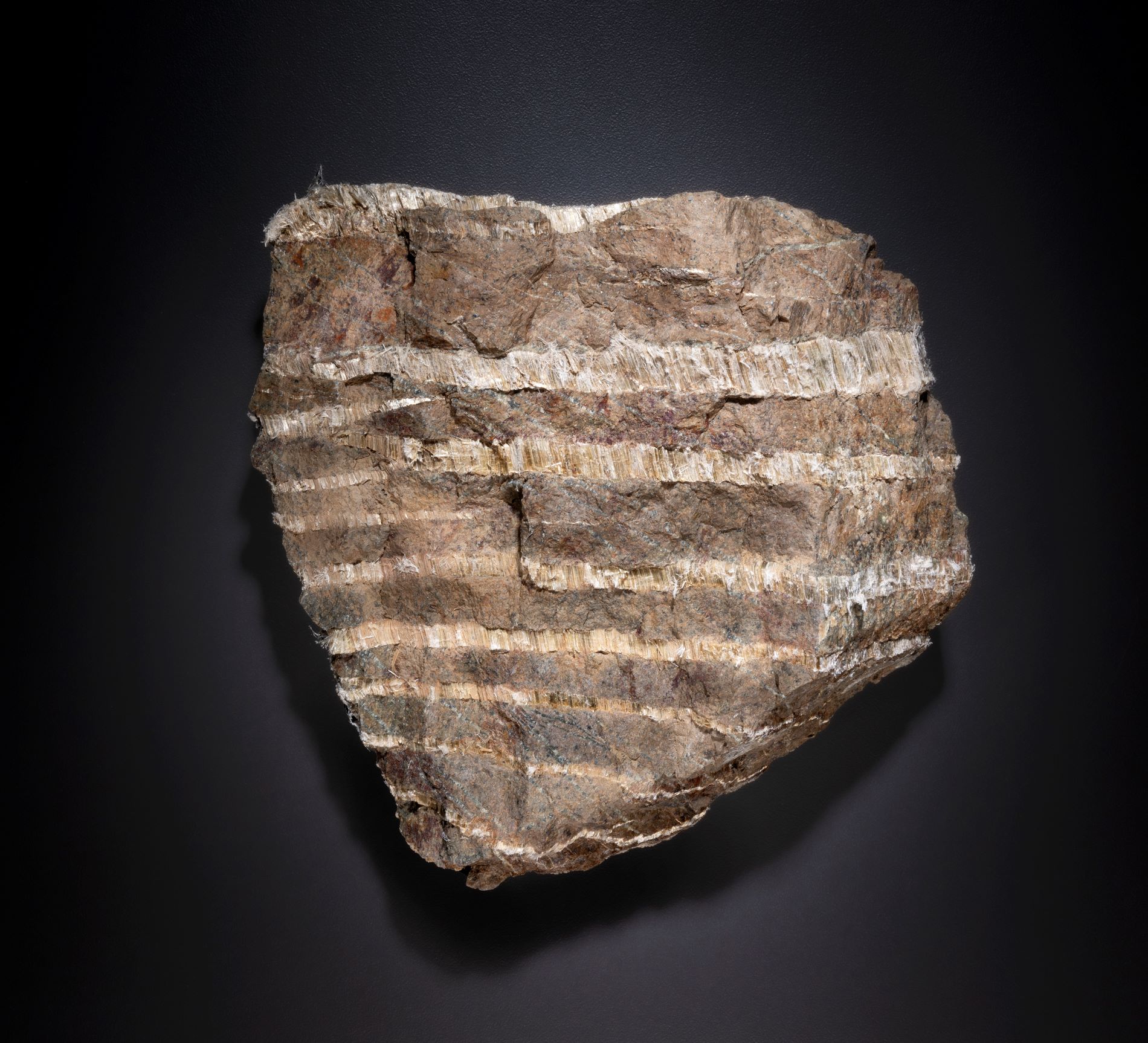

Chrysotile is the most common asbestos mineral. It forms when hot water seeps through magnesium-rich rocks called peridotites and develops chrysotile-rich veins that are mined for use in insulation, flooring, and roofing tiles. Exposure to chrysotile and other asbestos particles is not immediately toxic like the examples above, but inhalation of even small amounts causes irreversible damage to the lungs and can lead to lung cancer and death. For example, over the course of the 20th century, asbestos-contaminated vermiculite was mined in Libby, Montana, where miners and residents continue to suffer serious health consequences.

Layered seams of chrysotile are visible in this rock specimen collected in the Salt River District in Gila County, Ariz. (Photo/ Rick Wicker)

Radioactive substances are also common poisons because elements like uranium and polonium are unstable. Thus they decay from one radioactive element into another, releasing invisible cell-destroying radiation in the process. Colorado has some of the world's best deposits of these elements, which have been mined for radium, vanadium, and uranium since the 1870s.

One radioactive poison is particularly dangerous in Colorado. Anyone with a basement can be exposed to a toxic radioactive byproduct of uranium called radon. This invisible, tasteless, odorless gas accumulates in low areas because it is heavier than air. In our state, radon gas is extremely common because our soils have broken-down bits of granite in them, including fragments of uranium-rich mica. These release radon into the soil pore space. The gas can then migrate into your basement. Compounding the problem, radon also decays and binds to dust and other small particles readily trapped in the lungs. Once inside your body, these particles continue to emit cell-destroying radiation. Fortunately it is possible to test for radon levels and basement radon pumps eradicate the problem relatively easily.

Look for these and many other poisonous specimens on display, safely behind glass, in the Coors Gems and Mineral Hall.

Don't miss "The Power of Poison," now open at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. Admission is free for members.

A print version of this article was originally published in the Fall 2015 Edition of Catalyst.

This browser is no longer supported.

We have detected you are using a less secure browser - Internet Explorer.

Please download or use Google Chrome, Firefox or if using Windows 10, you may also use Microsoft's Edge browser.